The Battle of Antietam

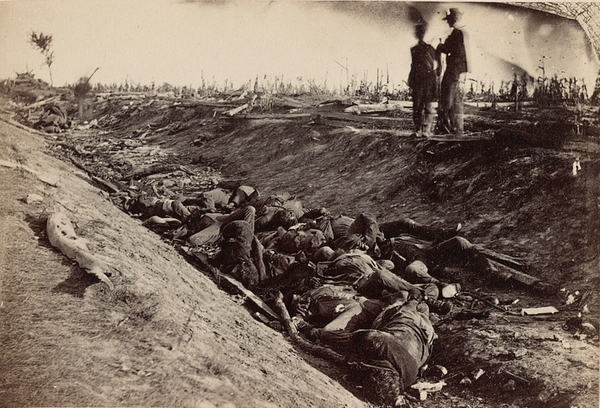

The Battle of Antietam, fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and along Antietam Creek, was a pivotal engagement in the American Civil War. It remains the single bloodiest day in American military history.

Armies Involved

Union Army:

- Army of the Potomac

- Commanded by Major General George B. McClellan

- Approximately 87,000 troops

Confederate Army:

- Army of Northern Virginia

- Commanded by General Robert E. Lee

- Approximately 38,000 troops (though this number varies due to desertions and stragglers)

Course of the Battle

The battle was the culmination of Lee’s first invasion of the North, part of the Maryland Campaign. Lee hoped to:

- Gain support from Maryland (a border state)

- Win a decisive victory on Union soil

- Influence upcoming midterm elections in the North

- Encourage diplomatic recognition from Britain or France

McClellan, having acquired a copy of Lee’s orders (Special Order 191), knew the Confederate army was divided. However, despite this intelligence advantage, McClellan failed to act decisively.

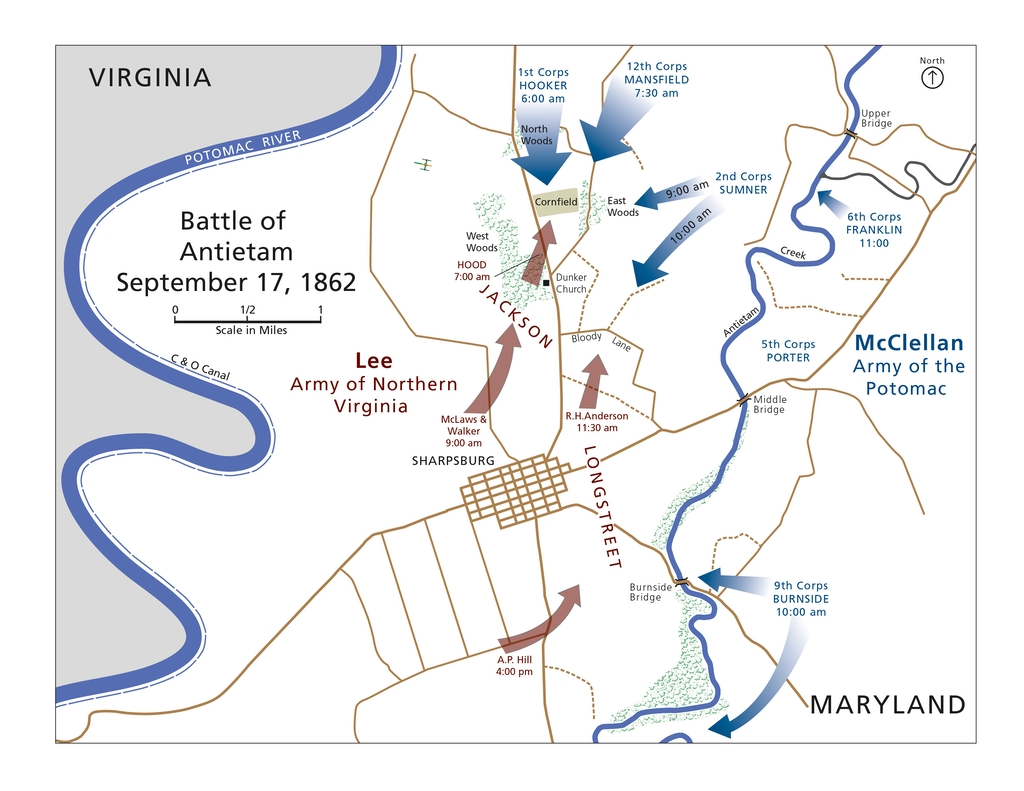

The battle unfolded in three main phases:

- Morning Phase: Heavy fighting in the Cornfield and around the Dunker Church.

- Midday Phase: Brutal combat at Bloody Lane, where Union forces attacked a sunken road defended by Confederates.

- Afternoon Phase: Union forces attacked the Burnside Bridge, a well-defended crossing over Antietam Creek. Eventually, they succeeded but were too slow to capitalize, as A.P. Hill’s division arrived from Harpers Ferry in time to repel the Union advance.

By nightfall, both armies remained on the field, exhausted and bloodied. Lee began retreating back into Virginia the next day, and McClellan did not pursue him aggressively.

Casualties

- Union: ~12,400 casualties

- Confederate: ~10,300 casualties

- Total: Over 22,700 casualties in a single day

Immediate Repercussions

Strategic Union Victory: Although tactically inconclusive, the battle was a strategic victory for the Union because it halted Lee’s invasion of the North.

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: President Abraham Lincoln used the outcome as an opportunity to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. It declared that enslaved people in rebelling states would be free as of January 1, 1863. This shifted the war’s focus from preserving the Union to abolishing slavery, giving it moral purpose and discouraging foreign support for the Confederacy.

Foreign Policy Impact: The Confederacy had hoped that Britain and France would recognize their independence. The Union’s success at Antietam and the proclamation significantly diminished the chances of foreign recognition or intervention.

Long-Term Repercussions

Military: McClellan’s failure to destroy Lee’s army led to increased frustration in Washington. He was eventually removed from command by Lincoln in November 1862.

Political: The battle and the Emancipation Proclamation gave the Union a moral high ground. However, it also polarized the North, with some Democrats opposing the war’s shift toward emancipation.

Moral and Human Toll: The immense casualties shocked the nation and foreshadowed the scale of bloodshed to come. It marked a turning point in perceptions of how long and costly the war would be.

Summary

The Battle of Antietam was a crucial moment in the Civil War — not because of territorial gain, but due to its strategic, political, and humanitarian consequences. It changed the character of the war and helped redefine the United States’ path forward, both as a union and as a nation confronting the issue of slavery.